Small, fast, and secretive - crakes and rails must rank as one of the more difficult species to observe and find across the world. Most species are cryptically plumaged, extremely shy, and loathe to fly - preferring to snake in and out of their preferred habitat, which is usually dense reeds, grasses, undergrowth.

On top of that, the best of these birds are often tiny. The members of this group of birds which a birder is most often acquainted with are heavy-bodied, conspicuous birds like swamphens, coots, and moorhens; so naturally, it is reasonable to expect the rest to be similar too. Alas, new birders - prepare to be surprised! I remember when I saw my first Baillon’s Crake as it dashed across a small puddle (in 2007), I was not prepared for the wee little sparrow-sized thing it was!

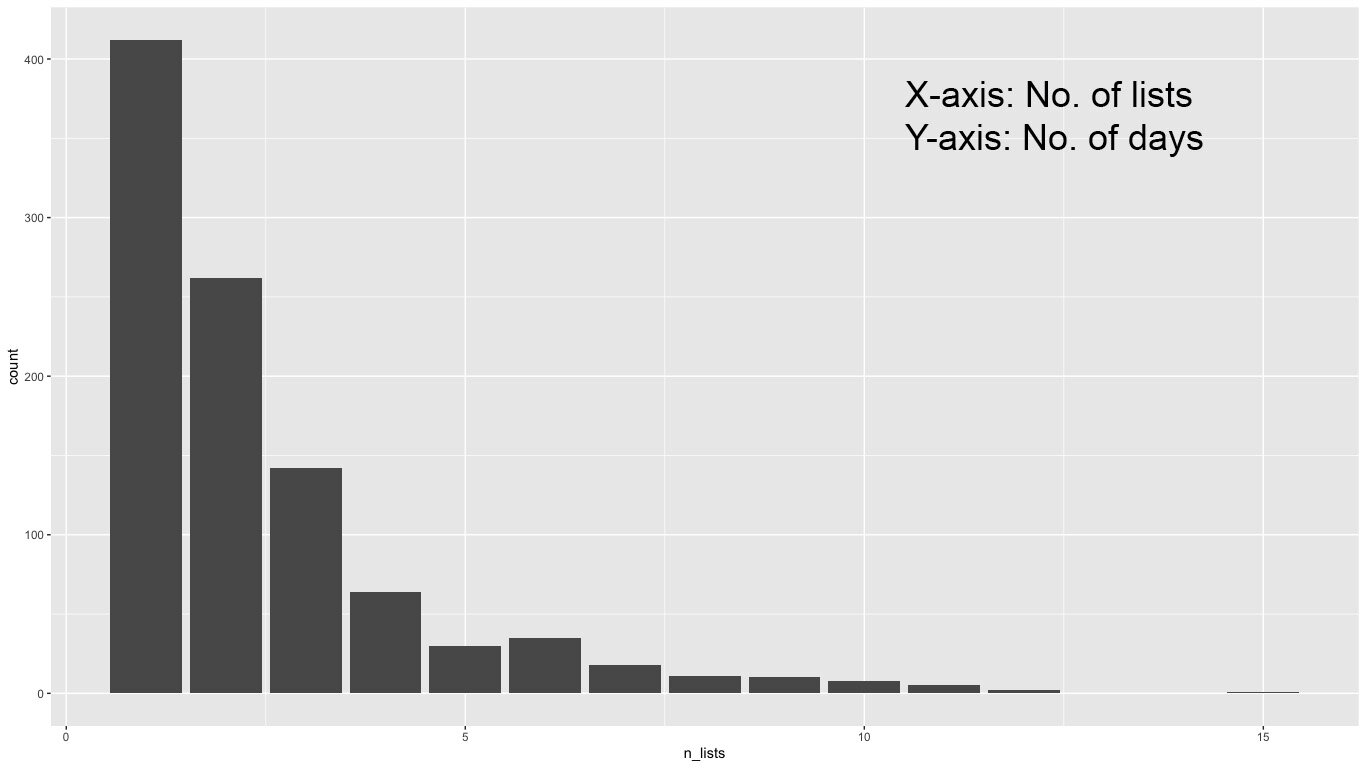

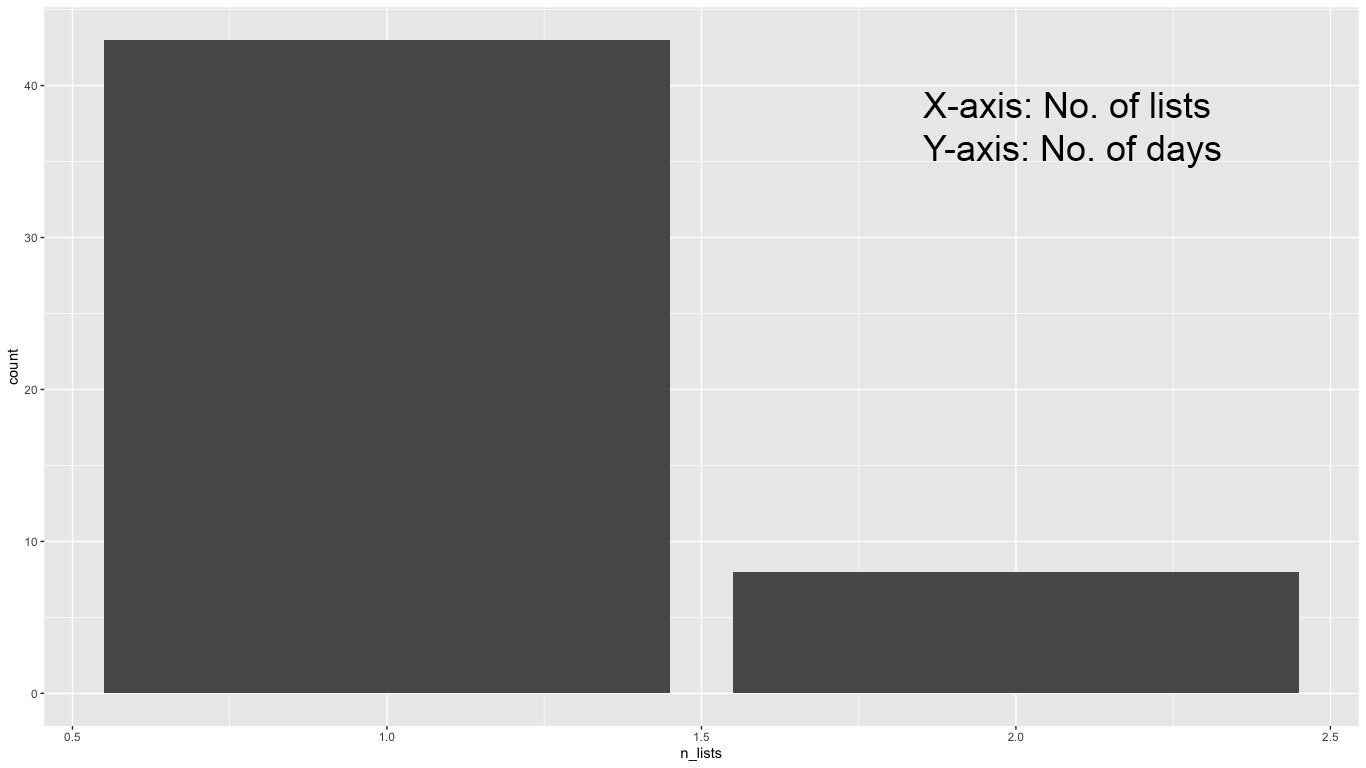

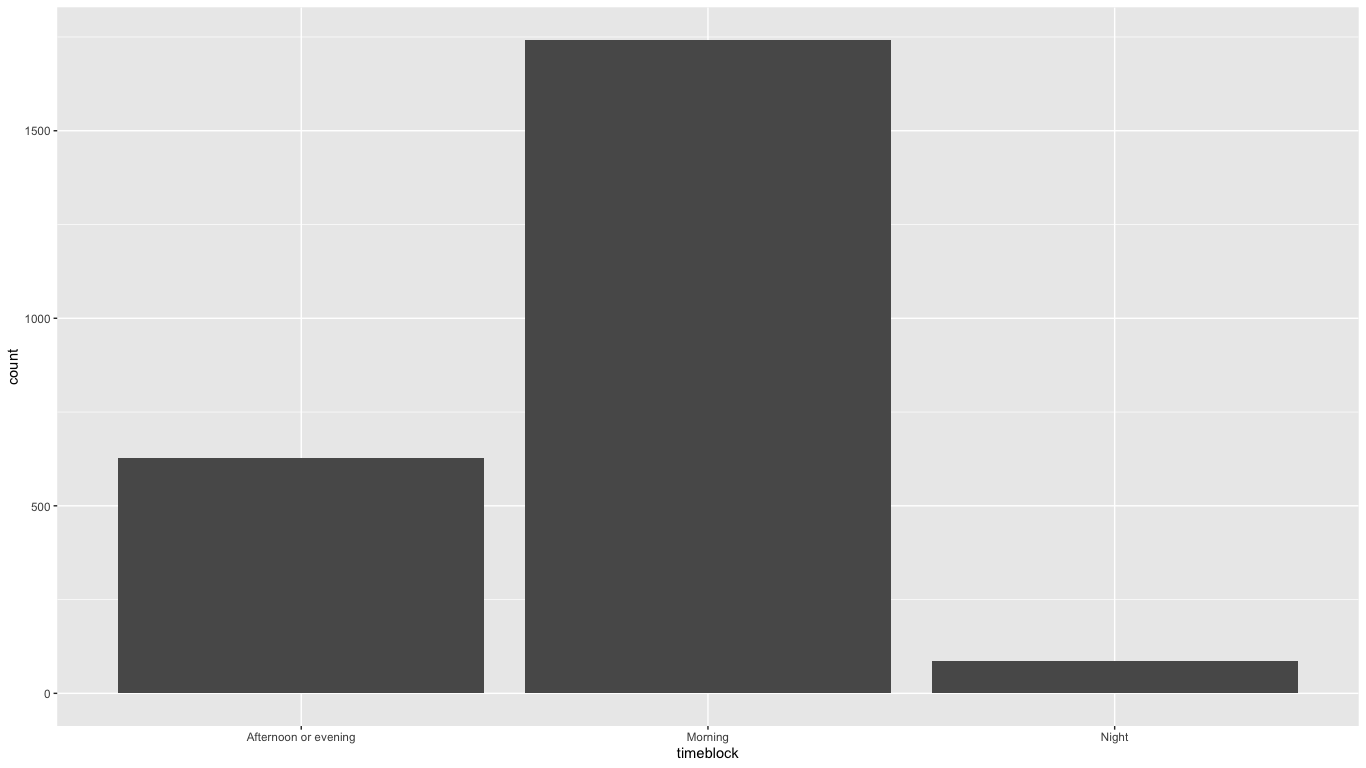

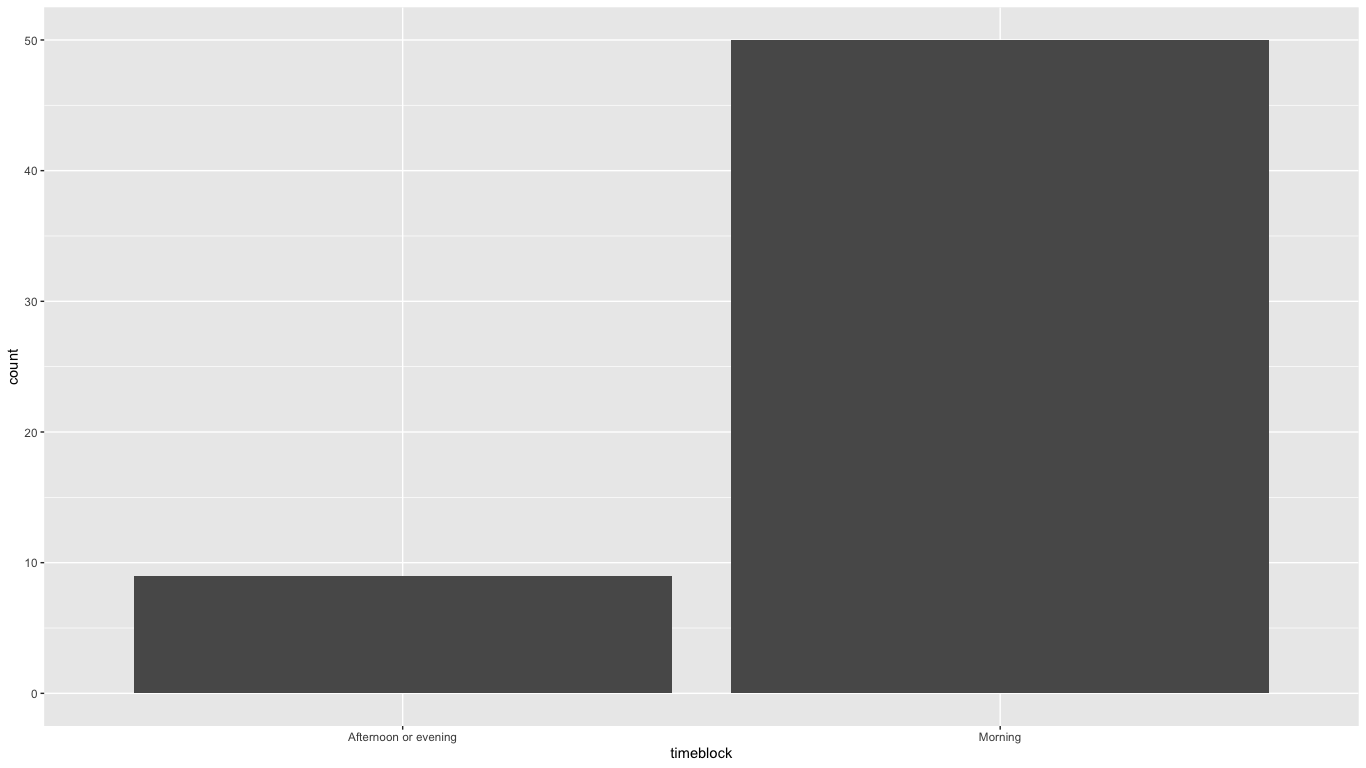

And like a lot of difficult-to-see and secretive birds, it’s very hard for researchers to ascertain how common or uncommon these species really are.

For all those reasons, sighting one is always an extremely rewarding experience. And for me, they’ll often be the highlight of any birdwatching trip.

In Tasmania, we regularly get to see 3 species of these secretive rails - Spotless Crake, Australian Crake, Lewin’s Rail (I’m not including the much commoner Australian Swamphen, Eurasian Coot, Tasmanian Nativehen, and the slightly uncommon Dusky Moorhen). But they seem to be, at best, uncommon and finding them can be quite hard. I consider myself lucky to even add them to my year list.

Spotless Crake

Lately, we have been lucky to find a reliable spot for Spotless Crakes along the NW Coast. The birds appear to be slightly more used to people walking on the path adjacent to their habitats. But most amazingly, it is the sheer density of the birds at the location that leaves me awestruck. Pairs apparently occupy tiny territories and, on an exceptionally good day, one may see up to 8 birds along a 300m stretch!

Spotless Crakes are tiny, mostly dark crakes that can be extremely skittish and skulking. They often feed on the margins of reeds where mud meets water and are quick to rush into cover when spotted. When viewed well, one can truly appreciate how pretty these crakes really are with their red eyes; and the subtle brown upperparts and grey underparts contrasting with the spots on the undertail.

Spotless Crake chick

When I visited the patch a day ago, my attention was initially drawn to 3 table tennis ball-sized fluffy birds that were out amongst the short grasses and mud. Spotless Crake juveniles! These little ones were soon joined by a pair of adults warily watching from the edges of vegetation. As I sat down while keeping them in view, the birds soon grew bolder and went about their business, ignoring my presence.

Face-off between two Spotless Crakes

Later, one of the adults from the pair with a chick seemed to have forgotten the rules of being a secretive bird and ventured out in the open, busying itself with picking out invertebrates from the mud. Another adult (yes, from a different pair of birds - told you the numbers were densely packed!) from the other side of this muddy patch clearly noticed the infringement by this individual and came running to let it know that territorial lines had been crossed! A short skirmish that included a weird almost ‘bird-of-paradise’-like-display (without the colours and flamboyance) followed as both the birds gave me an insight into their otherwise poorly-known lives. Quick video (see below) and some photos and it was all over in a <30 seconds.

I saw a lot of nice birds through the course of the morning (including Swift Parrots in the gums above me as I looked at the crakes) but this display took the cake :-)

Here’s a short video of the skirmish and a haiku to go with it:

Crakes at the border

Skirmishes, threats, and display

All wings, and no f(l)ight